The Moon is just about to enter Sagittarius this morning and will slowly apply to a square with Neptune and then a conjunction with Saturn, highlighting the Saturn/Neptune dynamic over the next day. Meanwhile Venus/Pluto and Sun/Mars are still approaching exact.

But let’s take a break from Venus/Pluto and Sun/Mars for the day and step back into the Saturn/Neptune dynamic, which I haven’t visited in my dailies for a while now (since the exact square started passing). The subject for today has to do with modeling. Are we using imaginative models of reality, or are we using lifeless models and then trying to compensate for their dryness with a kind of overstated emphasis on imagination?

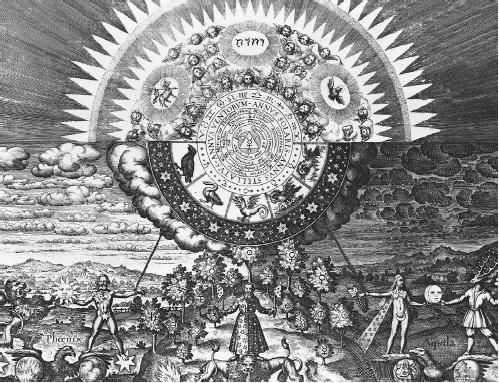

To illustrate, here are a few points that CS Lewis makes about the imagination of the medieval cosmos in his absolutely beautiful book “The Discarded Image.” In each point he is contrasting our “empirical” model of the heavens with certain versions of the imaginative model of the Ptolemaic cosmos in the west.

1. Whereas we perceive the heavens as covering vast and empty distances of silent black space between remote objects, the ancient cosmos was perceived as a series of spheres, filled with celestial/divine beings, colors, kingdoms, light, and never ending adoration music, ascending toward the primum mobile, the highest sphere which was the generative motion of the cosmos that moved everything round and round, beyond which was God or the unmoved mover.

The cosmos in the higher spheres above earth moved in predictable, steady, cyclical motion, moved by their intellectual love of the creator. By using the word “intellectual” we mean that their nature echoed or was closer to an embodied understanding of the absolute or the unmoved mover: the eternal. As the ascension continued upward there were hierarchies of angelic intelligences who were turned toward mankind and others turned toward God. Those turned toward god were like a never ending glorious song of adoration, circling in time an echo of divine understanding, which trickled down through the lower levels of intelligence all the way down to earth and would show humans how to create thsame harmony and love on earth through religious or contemplative life and the harmonious organization of society.

Even the darkness of night in the old model was seen as the conical projection of the earth’s shadow. Whereas the daytime Sun illuminated the heavens and showed us the true reality of all the heavenly spheres (bathed in light), it also set us at the boundary, outside the wall of the heavenly kingdoms. When night came we were therefore looking up, “through darkness but not at darkness.” We were listening through the mute of our mind’s silencing of the higher realms…not that space itself was vacuous. Not surprisingly Lewis wrote a science fiction novel called, “Out of the Silent Planet.”

It wasn’t necessarily important that this model was “literal,” Lewis says, but rather that it was itself a display of intellectual adoration…it’s creation echoed the same kind of song that the spheres were thought to be singing because of their own higher understanding of love. CS Lewis points this out by saying that it’s really a shame we lost the imagination of the model, because models were understood as models or intellectual songs of worship and beauty, whereas today they are considered only for their empirical “validity.”

2. When we think of the universe having certain “laws,” we generally conceive of these laws like a police state. We think of “obedience” and it brings up all our issues with authority and the abuse of authority. In the ancient cosmos the idea of law was more closely related to what Lewis describes as “Sympathies, antipathies, and strivings.” Lewis writes, “Everything has its right place, its home, the region that suits it, and, if not forcibly restrained, moves thither by a sort of homing instinct.”

So, the Moon strives toward or has sympathy toward certain things…there is a celestial realm of the zodiac that suits it, etc. These aren’t rules in the sense of a police state but rather inclinations, and natural strivings that resonate from the planet, as in a kind of love or song. But these also weren’t to be taken too literally. As Lewis writes, “On the imaginative and emotional level it makes a great difference whether, with the medievals, we project upon the universe our strivings and deisres, or with the moderns, our police-system and our traffic regulations. The old language continually suggests a sort of continuity between merely physical events and our most spiritual aspirations.”

3. When we think of the cosmos nowadays we often come to the word “infinite.” But Lewis writes of the importance of the traditional cosmos being understood as finite. He writes, “For thought and imagination, ten million miles and a thousand million miles are much the same. Both can be conceived (that is, we can do sums with both) and neither can be imagined; and the more imagination we have the better we shall know this. The really important difference is that the medieval universe, while unimaginably large, was also unambiguously finite. And one unexpected result of this is to make the smallness of the Earth more vividly felt. In our universe she is small, no doubt; but so are the galaxies, so is everything–and so what? But in theirs there was an absolute standard of comparison. The furthest sphere, Dante’s maggior corpo is, quite simply and finally, the largest object in existence. The word “small” as applied to Earth thus takes on a far more absolute significance. Again, because the medieval universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape, containing within itself an ordered variety. Hence to look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest–trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building. The ‘space’ of modern astronomy may arouse terror, or bewilderment or vague reverie; the spheres of the old present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony. That is the sense in which our universe is romantic, and theirs was classical. This expalins why all sense of the pathless, the baffling, and the utterly alien–all agoraphobia–is so markedly absent from medieval poetry when it leads us, as so often, into the sky.”

——-

Regardless of whether or not we agree with Lewis on all the above points, or if we value the imaginative beauty of the various medieval/ancient views of the cosmos listed above, what I’ve been noticing about this Saturn/Neptune transit is the importance of looking at the imaginative value of our models. What models do we hold when we look above us–do we even have a working idea or image of the cosmos beyond the fluctuations of our personal thoughts and actions and emotions and opinions? Even if we are deeply reflective/psychological people, how does our privileging of psychological reflection model the cosmos in which it finds itself psychologizing?

I admire people like Richard Tarnas and Steven Forrest and Robert Hand who are actively working not just toward methods of character, behavior, personal growth or psychological description in the birth chart but who are also taking on celestial modeling and it’s importance to the human imagination. Especially since we live in a time when our cosmos has been largely disenchanted by modern empiricism. In my own studies I am finding that a deeper study of the traditional cosmos is helping me to see astrology with new eyes…eyes that see intelligent and beautiful music playing ceaselessly in the heavens, and eyes that see a towering but diverse structure…one in which my mind finds harmony and rest..no shortage of diversity and all laws ringing out like call and response music rather than traffic regulations taking place in an empty, cold, and silent space above or beyond me.

Granted, there is nothing wrong with either space or silence or emptiness…but my feeling is that even space and silence and emptiness may need revising for the sake of the imagination of many people on our planet…whose experience of silence and space and emptiness above are not nearly alive and musical enough within.

Prayer: Help us to feel held by the cosmos we look up at, until it comes to rest the busy mind within, a call and response that’s been sung for as long as time has been the moving image of eternity.

But let’s take a break from Venus/Pluto and Sun/Mars for the day and step back into the Saturn/Neptune dynamic, which I haven’t visited in my dailies for a while now (since the exact square started passing). The subject for today has to do with modeling. Are we using imaginative models of reality, or are we using lifeless models and then trying to compensate for their dryness with a kind of overstated emphasis on imagination?

To illustrate, here are a few points that CS Lewis makes about the imagination of the medieval cosmos in his absolutely beautiful book “The Discarded Image.” In each point he is contrasting our “empirical” model of the heavens with certain versions of the imaginative model of the Ptolemaic cosmos in the west.

1. Whereas we perceive the heavens as covering vast and empty distances of silent black space between remote objects, the ancient cosmos was perceived as a series of spheres, filled with celestial/divine beings, colors, kingdoms, light, and never ending adoration music, ascending toward the primum mobile, the highest sphere which was the generative motion of the cosmos that moved everything round and round, beyond which was God or the unmoved mover.

The cosmos in the higher spheres above earth moved in predictable, steady, cyclical motion, moved by their intellectual love of the creator. By using the word “intellectual” we mean that their nature echoed or was closer to an embodied understanding of the absolute or the unmoved mover: the eternal. As the ascension continued upward there were hierarchies of angelic intelligences who were turned toward mankind and others turned toward God. Those turned toward god were like a never ending glorious song of adoration, circling in time an echo of divine understanding, which trickled down through the lower levels of intelligence all the way down to earth and would show humans how to create thsame harmony and love on earth through religious or contemplative life and the harmonious organization of society.

Even the darkness of night in the old model was seen as the conical projection of the earth’s shadow. Whereas the daytime Sun illuminated the heavens and showed us the true reality of all the heavenly spheres (bathed in light), it also set us at the boundary, outside the wall of the heavenly kingdoms. When night came we were therefore looking up, “through darkness but not at darkness.” We were listening through the mute of our mind’s silencing of the higher realms…not that space itself was vacuous. Not surprisingly Lewis wrote a science fiction novel called, “Out of the Silent Planet.”

It wasn’t necessarily important that this model was “literal,” Lewis says, but rather that it was itself a display of intellectual adoration…it’s creation echoed the same kind of song that the spheres were thought to be singing because of their own higher understanding of love. CS Lewis points this out by saying that it’s really a shame we lost the imagination of the model, because models were understood as models or intellectual songs of worship and beauty, whereas today they are considered only for their empirical “validity.”

2. When we think of the universe having certain “laws,” we generally conceive of these laws like a police state. We think of “obedience” and it brings up all our issues with authority and the abuse of authority. In the ancient cosmos the idea of law was more closely related to what Lewis describes as “Sympathies, antipathies, and strivings.” Lewis writes, “Everything has its right place, its home, the region that suits it, and, if not forcibly restrained, moves thither by a sort of homing instinct.”

So, the Moon strives toward or has sympathy toward certain things…there is a celestial realm of the zodiac that suits it, etc. These aren’t rules in the sense of a police state but rather inclinations, and natural strivings that resonate from the planet, as in a kind of love or song. But these also weren’t to be taken too literally. As Lewis writes, “On the imaginative and emotional level it makes a great difference whether, with the medievals, we project upon the universe our strivings and deisres, or with the moderns, our police-system and our traffic regulations. The old language continually suggests a sort of continuity between merely physical events and our most spiritual aspirations.”

3. When we think of the cosmos nowadays we often come to the word “infinite.” But Lewis writes of the importance of the traditional cosmos being understood as finite. He writes, “For thought and imagination, ten million miles and a thousand million miles are much the same. Both can be conceived (that is, we can do sums with both) and neither can be imagined; and the more imagination we have the better we shall know this. The really important difference is that the medieval universe, while unimaginably large, was also unambiguously finite. And one unexpected result of this is to make the smallness of the Earth more vividly felt. In our universe she is small, no doubt; but so are the galaxies, so is everything–and so what? But in theirs there was an absolute standard of comparison. The furthest sphere, Dante’s maggior corpo is, quite simply and finally, the largest object in existence. The word “small” as applied to Earth thus takes on a far more absolute significance. Again, because the medieval universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape, containing within itself an ordered variety. Hence to look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest–trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building. The ‘space’ of modern astronomy may arouse terror, or bewilderment or vague reverie; the spheres of the old present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony. That is the sense in which our universe is romantic, and theirs was classical. This expalins why all sense of the pathless, the baffling, and the utterly alien–all agoraphobia–is so markedly absent from medieval poetry when it leads us, as so often, into the sky.”

——-

Regardless of whether or not we agree with Lewis on all the above points, or if we value the imaginative beauty of the various medieval/ancient views of the cosmos listed above, what I’ve been noticing about this Saturn/Neptune transit is the importance of looking at the imaginative value of our models. What models do we hold when we look above us–do we even have a working idea or image of the cosmos beyond the fluctuations of our personal thoughts and actions and emotions and opinions? Even if we are deeply reflective/psychological people, how does our privileging of psychological reflection model the cosmos in which it finds itself psychologizing?

I admire people like Richard Tarnas and Steven Forrest and Robert Hand who are actively working not just toward methods of character, behavior, personal growth or psychological description in the birth chart but who are also taking on celestial modeling and it’s importance to the human imagination. Especially since we live in a time when our cosmos has been largely disenchanted by modern empiricism. In my own studies I am finding that a deeper study of the traditional cosmos is helping me to see astrology with new eyes…eyes that see intelligent and beautiful music playing ceaselessly in the heavens, and eyes that see a towering but diverse structure…one in which my mind finds harmony and rest..no shortage of diversity and all laws ringing out like call and response music rather than traffic regulations taking place in an empty, cold, and silent space above or beyond me.

Granted, there is nothing wrong with either space or silence or emptiness…but my feeling is that even space and silence and emptiness may need revising for the sake of the imagination of many people on our planet…whose experience of silence and space and emptiness above are not nearly alive and musical enough within.

Prayer: Help us to feel held by the cosmos we look up at, until it comes to rest the busy mind within, a call and response that’s been sung for as long as time has been the moving image of eternity.

Leave a Reply